RUNNING WITH THE BULLS

Hemingway, Bullfighting, and the Lost Generation

What depictions of bullfighting in Hemingway’s enduring classic, “The Sun Also Rises,” tell us about masculinity in post-World War I Europe.In the years following World War I, thousands of American men came back from Europe scarred, isolated, and disillusioned. When they left in April 1917, romanticized images of heroic battles and Arthurian bravery filled their heads. But after reality set in however, these ruggedly romanticized dreams were shattered. The gallant men these boys imagined themselves to be were replaced with gaunt and frightened skeletons. Among these men was celebrated author, Ernest Hemingway. Born on July 21, 1899 in Oak Park, Illinois, Hemingway grew up spending summers on Walloon Lake in Northern Michigan where his father took him on hunting, fishing, and camping excursions that would fuel Hemingway’s lifelong love of the great outdoors. These outdoor excursions would also fuel a lifelong propensity to over-assert his own manhood and become, as journalist Allen Barra puts it: a “bully, braggard, and myth-monger.”

Ernest Hemingway with Lady Duff Twysden, Harold Loeb, Hadley Richardson, Ogden Stewart, and Pat Guthrie at a cafe in Pamplona, Spain during the Fiesta of San Fermin in July, 1925. Ernest Hemingway stationed in Milan, 1918. Ernest Hemingway Photograph Collection, Kennedy Library)

Throughout the 1920’s, during Warren G. Harding’s so-called “return to normalcy,” many young men like Hemingway desperately searched for their own return to normalcy— which included a search for what they felt was their lost manhood. The writers who gave voice to this group were famously referred to by Gertrude Stein as “the Lost Generation.” Alongside other literary luminaries like F. Scott Fitzgerald, one of the many ways in which Hemingway and other members of the Lost Generation sought to reclaim their lost manhood was by traveling back to Europe, as depicted in several of Hemingway’s stories and novels. As Hemingway’s novel The Sun Also Rises depicts, one of the ways in which these men entertained themselves while in Europe was by watching bullfights. As Jake Barnes, the narrator of The Sun Also Rises, says: “we often talked about bulls and bull-fighters… It was simply the pleasure of discovering what we each felt.” In this context, the “we” Jake refers to is himself and his male friends— also World War I veterans.

Bulls and bullfighting are essential to our understanding of masculinity in many of Hemingway’s most famous works, but especially in The Sun Also Rises. In the novel, Jake sees the bullfights as a means to reclaim his manhood; yet, he loses the woman he loves, Lady Brett Ashley, to bullfighter, Pedro Romero. Furthermore, like a bull that is castrated after it is deemed not good enough to fight, Jake has a war wound, which has rendered him impotent. The bullfighting depicted in The Sun Also Rises serves then, as a representation of World War I’s detrimental effect on the Lost Generation’s idea of manhood.

Unsurprisingly, Hemingway was a great fan of bullfighting. Aside from The Sun Also Rises, Hemingway wrote about the practice and traditions of Spanish bullfighting in Death in the Afternoon and the posthumously published The Dangerous Summer. In Death in the Afternoon, Hemingway states that bullfighters are the best of men because of “the skill and courage they must use to overcome this danger” of bullfighting.

“… and Gilgamesh thrust his sword with the skill of a butcher between the shoulders and horns, and they killed the bull”

In this passage, heroes Gilgamesh and Enkidu, defeat the Bull of Heaven sent by the God, Anu, to kill them, showing that even in human history’s earliest writing, it takes an epic hero— the paragon of masculinity— to conquer a bull. Bullfighting, or what would become bullfighting, continued well into the Roman Empire where gladiators were often tasked with killing a bull in the arena. In medieval Spain, bullfighting became a sport for the rich and enjoyed by the likes of rulers from Charlemagne to Emperor Charles V. By the eighteenth century, famous bullfighters like Francisco Romero would be paid large sums of money in sponsorship for their bullfights and eventually matadors like Juan Belmonte, helped popularize the dangerous version of Spanish Bullfighting depicted in The Sun Also Rises that we know today.

The common thread in the history of bullfighting appears to be that bullfighting is considered a male pastime (despite the accomplishments of celebrated female matadors like Conchita Cintrón and Nicolasa Escamilla) and moreover, centered on male dominance. For the matador to win, he must assert dominion over the castrated bull by destroying it. In fact, bullfighting was so strongly associated with men and masculinity that in the late nineteenth century, when activists moved to ban bullfighting in Spain, they were charged with “attempting to feminize Spain” and any other form of public entertainment that wasn’t bullfighting was “effeminate and degrading.” Given the emphasis on men in bullfighting, it comes as no surprise that Hemingway’s male characters in The Sun Also Rises use it as a way to reclaim their lost manhood.

Bullfighter Juan Belmonte in Spain holding a muleta (small cape) in one hand and a sword in the other. Barnaby Conrad, Britannica.

In this context, Jake Barnes is certainly more bull than bullfighter. In bullfighting, bulls that are deemed unfit to fight are castrated and sent to nearby ranches to aid in the training of other bulls that will eventually go on to fight. Like a castrated bull, Jake has suffered from an undisclosed war injury that has rendered him impotent and unable to perform sexually. When Jake reflects on his time recovering in an Italian hospital, he remembers the liaison colonel saying “you… have given more than your life,” implying that impotence and being unable to successfully make love to a woman is a fate worse than death. Jake claims to “play it along and just not make trouble for people,” so as to keep his injury, or more accurately, lack of masculinity, a secret from people and adds that he “never would have had any trouble if [he] hadn’t run into Brett when they shipped [him] to England.” Brett is then Jake’s scapegoat for his inability to feel like a real man since he desires her sexually but knows nothing can come of it due to his impotence.

While Jake tries to have a sense of humor about the situation, even telling Brett that “what happened to [him] is supposed to be funny,” he knows in his heart that “certain injuries or imperfections are a subject of merriment while remaining quite serious for the person possessing them.” In other words, Jake can put on a brave front and be a man in a performative way, but believes his injury keeps him from ever being a true man again. In this way, Jake is a steer, or cabestro. He has a bodily imperfection caused by an external force which prevents him from being able to grow into a toro, or fighting bull. While Jake’s war injury makes him a steer, Pedro Romero, the bullfighter who eventually wins Lady Brett, is not only symbolic of the toro, but of World War I entirely. The war was one of the most violent and devastating atrocities the world had known at the time and people who fought in, or were present on the battlefields, ended up dead, injured, or utterly broken— not unlike a bull that returns from the bull ring severely injured or prepped for the slaughterhouse. When Jake and Bill first go to see one of his bullfights, Jake says that he and Bill are “very excited about Pedro Romero,” adding that this bullfight was a real one and that “there had not been [a real one] for a long time.” This excitement about Romero on Jake and Bill’s part mirrors that of many young men who went off to fight before World War I. When they went to fight however, many were met with parades and extensive pageantry. Like the romanticized image of the war, Romero is a gallant and heroic symbol of manhood.

U.S. World War I propaganda posters, 1917. Smithsonian.

In both war and bullfighting a man who wins can automatically achieve a lifetime of glory. Since Jake is the bull in this narrative however, Jake’s excitement and energy upon getting to know Romero quickly deteriorates when reality sets in. When Mike tells Cohn that Brett is off somewhere with Romero and jokingly adds that she and Romero are “on their honeymoon,” the three male friends end up in a fist-fight. Like armies in battle, the men throw punches until someone breaks them up. Furthermore, just as World War I maimed, mutilated, and destroyed its soldiers, Romero maims, mutilates, and destroys his bulls in the ring. In one of the bullfights detailed in the novel, Romero kills a bull and has the bull’s ear cut off “by popular acclamation and given to [him]” as if it were a spoil of war. This particular practice of taking the bull’s ear harkens back to classical mythology in which heroes and soldiers brought back the heads of their enemies, like Perseus bringing back the head of Medusa to Polydectes. To Romero, the bull is nothing but a monster to kill and in one of the final fights described, Romero drives his knife into a bull and has his brother cut the ear off to the delight of the crowd. In this way, Romero’s bullfights are certainly no different from antiquated depictions and ideas of warfare in which the victor gets to be the hero. Romero’s heroism and ideal masculinity cause Brett to fall for him and leave Jake lost. Romero is just another force in Jake’s life that has caused him to feel like his manhood, and his purpose, is lost forever.

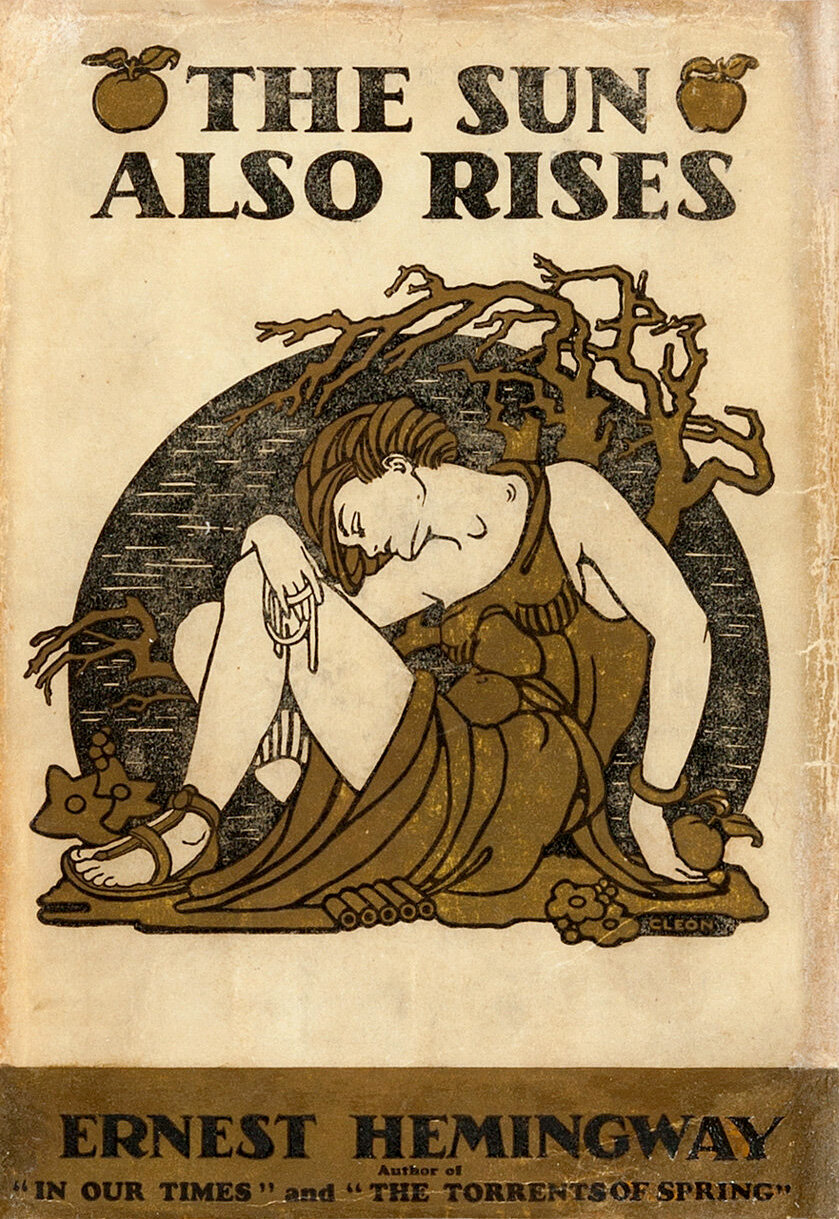

First edition cover of The Sun Also Rises, 1926, designed by Cleonike Damianakes. Heritage.

This sense of losing one’s purpose runs rampant in The Sun Also Rises, as it does in many other Hemingway novels like 1929’s A Farewell to Arms. Jake wants to feel like himself again and feels that Brett is the way to do so. When Brett chooses the daring and brave Romero over the lost and broken Jake, Jake feels incomplete. Indeed, after having fought in a war Jake should be thought every bit as heroic as Romero is. The only difference between them, is that Romero is able to sexually satisfy her. Jake on the other hand has been rendered impotent and while women can find him attractive, his inability to consummate a relationship renders him incomplete as a man. The bullfights ultimately become a visual representation of how a man’s inability to conquer his enemy can destroy his reputation. If Romero, the dashing bullfighter, is the war and Jake is the bull, then the bullfight itself is the overall process of being a soldier. A man enters the war like a bull in the ring, uncertain, excited, and agitated, but ready to fight to the death. At one point in the novel, Romero goes as far as to say that he is “never going to die” and calls the bulls his “best friends.” When Brett asks if Romero would really “kill [his] friends,” Romeo responds: “Always… so they don’t kill me.” This moment perfectly encapsulates the nature of war that Hemingway’s work demonstrates his great understanding of — destroy and kill anyone, including those closest to you, before you are killed yourself. The Sun Also Rises is reveals the true nature of manhood in the 1920’s: in order to maintain a masculine image, he must either win, die a hero, or live the rest of his life in shame.

Sources and References:

Burns, Kevin and Lynn Novick, directors. Hemingway. Florentine Films and WETA, 2021.

Hemingway, Ernest. Death in the Afternoon. Edited by Simon & Schuster, Simon & Schuster, 2014.

Hemingway, Ernest. The Sun Also Rise: The Hemingway Library Edition. Edited by Sean Hemingway, Scribner, 2014.

Shubert, Adrian. Death and Money in the Afternoon: A History of the Spanish Bullfight. Oxford University, 1999.

Unknown. The Epic of Gilgamesh. Edited by David Ferry, Penguin, 2014.