Gin, Guns, and Gadgets

the real James Bond Story

A look into the complex legacy and thrilling history of 007 and his enigmatic creator, Ian FlemingA well-dressed Englishman struts into a casino. Tall, dark-haired, and charming in an expensive suit, he takes a sip of his martini— shaken, not stirred— and a long, pensive drag off his custom made cigarette. On his arm, rests a gorgeous woman with ruby lips and a matching silk evening gown. Whether in a Sean Connery classic or a Daniel Craig box-office smash, scenes like this are the hallmark of any James Bond movie. They were also quite commonplace in the life of 007’s creator, Ian Fleming.

For nearly seventy years, the James Bond novels and films have captivated audiences across the world with their exotic locations, daring action scenes, twisted villains, stunning couture, and never ending parade of attractive faces. But where did these thrilling adventures come from? Were they the product of one man’s overactive imagination, or were they the heavily fictionalized accounts of nearly twenty years spent working in international reporting and espionage?

The answer is, of course, both. Indeed, the life of 007’s creator was filled with just as much intrigue as his fictional avatar’s— and equally as packed with sex, style, guns, gadgets, and cocktails. In other words, all the ingredients for a perfect film franchise. And at the center of this perfect franchise, stands a hero who (much like his creator did in his life), has endured. Since his literary debut in 1953, the popular British spy has gone through several incarnations from Sean Connery’s untamable playboy, Roger Moore’s comical rebel, to Daniel Craig’s gritty warrior. In fact, the latest of these incarnations, No Time To Die, is set for release later this year. Despite these differences in characterization, each version retains that indelible flair of Ian Fleming’s and has, for better and for worse, served as a beacon of escape and a model of masculinity for generations.

***

“He developed a reputation as a rebel before the age of five and also showed clear signs of developing the same restlessness that would follow him throughout the rest of his life.”

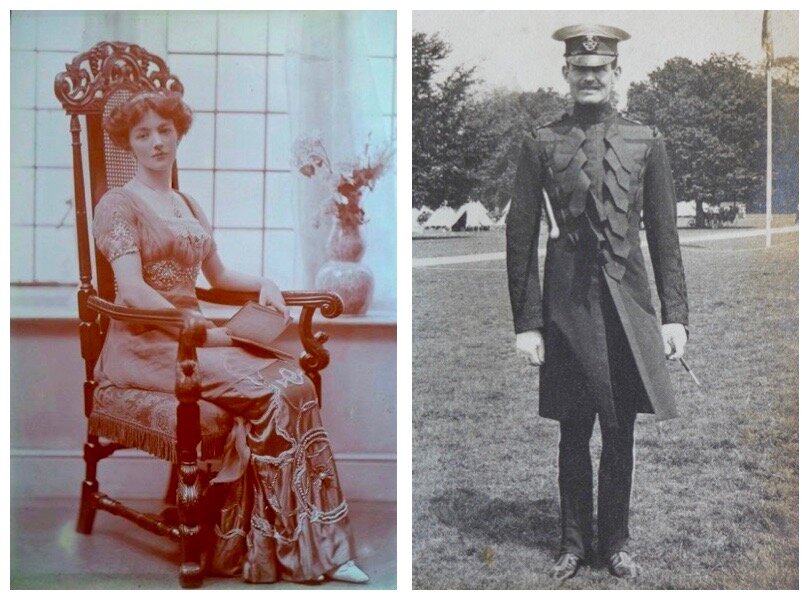

L: Evelyn Fleming at her society debut, R: Valentine Fleming in uniform during WWI (Ian Fleming Estate)

Born to an aristocratic English family, Fleming’s journey from the austere boarding schools of his youth to the dangerous battlegrounds of the European front in World War II mirrored the life of his popular hero in many ways.

Though Bond was orphaned at an early age, Fleming grew up with his mother, Evelyn St. Croix Fleming, and his father, Valentine Fleming. Evelyn was a well known socialite, while Valentine was Conservative MP for the Henley Division of South Oxfordshire. Adding to Ian’s prestigious pedigree was his grandfather, Scottish financier Robert Fleming. By all accounts, Ian’s childhood in the English countryside was simple and idyllic— with days spent searching caves, forests, and beaches for precious stones. He developed a reputation as a rebel before the age of five and also showed clear signs of developing the same restlessness that would follow him throughout the rest of his life. Fleming would eventually reflect on his pastoral childhood days in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service by using Bond to remember their gentle simplicity.

“the painful grit of wet sand between young toes when the time came for him to put his shoes and socks on, of the precious little pile of seashells…”

The onset of World War I however, would upend this perfect life when he was just six years old.

Fleming at play on the beach (Ian Fleming Estate)

After Valentine Fleming enlisted, he was swiftly made a major before being killed by German shelling on May 20, 1917. Though Fleming always claimed to not remember his father, a glowing obituary from none other than Winston Churchill himself cements Val Fleming’s reputation as a war hero— the same sort that Fleming himself longed to be.

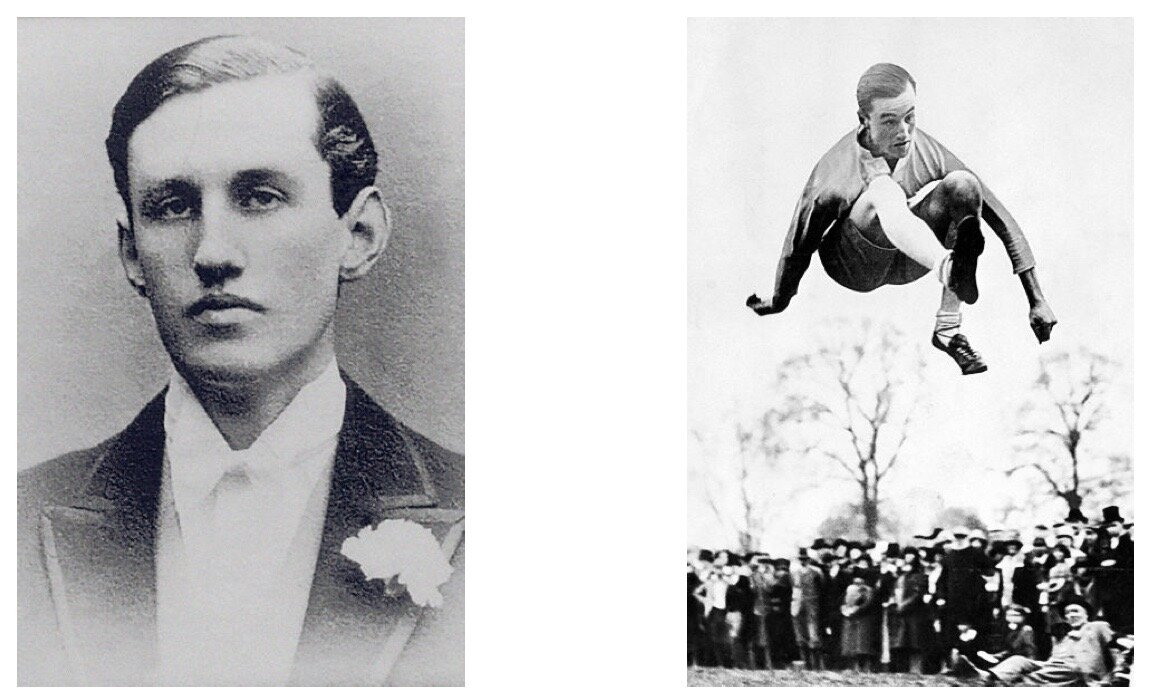

At thirteen, Fleming began attending Eton College, the prestigious school that counts popes, archbishops, noblemen, celebrities, and royalty among its distinguished graduates. While not academically gifted, Fleming found a knack for sports and writing, twice earning the title of Victor Ludorum (“Winner of the Games”) and publishing the short story, “The Ordeal of Caryl St. George.” While at school, Ian frequently clashed with E.V. Slater, his housemaster who (much like Bond’s M) disapproved of Fleming’s raucous attitude. Like Bond, Fleming was also obsessed with his hair oils, his cars, and his relationships with women. Whether it was the boy’s devil-may-care attitude, or out of genuine care, Slater eventually requested Fleming be removed from Eton a term early and be sent to train at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst. True to the scandalous reputation he’d cultivated, Fleming left Sandhurst after less than a year due to having contracted gonorrhea.

L: Fleming’s “Leaving Portrait,” Eton College, 1926. R: “Winner of the Games” at Eton College (Ian Fleming Estate)

For the next several years, Fleming would lead a life James Bond himself would’ve been proud of. In the hopes of entering her son into Foreign Service, Evelyn sent her son to the Tennerhof in Kitzbühel, Austria in 1927. There, he sharpened his language skills under the watchful eye of former British spy, Ernan Forbes Dennis. While attending the University of Geneva, Fleming began a passionate romance with a young woman by the name of Monique Panchaud de Bottens. In no time, Panchaud de Bottens and Fleming were engaged and Evelyn, shocked at her son’s impulsive proposal, took matters into her own hands.

With no prospects, Evelyn pulled several strings to get her son a job as a reporter for Reuters. By October 1931, Fleming’s superior writing skills and ability to file his stories before other agencies garnered him a position as a sub-editor. Impressed by his skills, one agency sent a telegram to Reuters, writing:

“We fellow journalists have extremely high opinion of his journalistic ability. He has given us all a run for our money.”

At Reuters, Fleming reveled in writing about international affairs and motor racing— both of which would be trademarks of the Bond series. In 1933, Fleming travelled to Moscow, where he was tasked with covering a trial of six engineers from the British company Metropolitan-Vickers. While the trial itself was a sham and the six engineers were convicted, Fleming nonetheless appealed to the ruthless Stalin for an interview. Reportedly, Fleming received a personal note signed by the dictator himself politely declining the offer.

Fleming’s career in international affairs would not end after this interaction. After cutting off his engagement to Monique Panchaud de Bottens at the behest of his mother (who threatened to cut him off financially), Fleming reluctantly became a stockbroker for Rowe and Pittman on Bishopgate. While he had been a skilled writer for Reuters, he proved to be a rather inept stockbroker. In fact, he was so bad, that his own estate posthumously referred to him as “the World’s Worst Stockbroker.”

In 1939 however, just before the outbreak of World War II, the British Government sought out Fleming at his stockbroker’s job and asked him to accompany a minister on a trade mission. Fleming was given cover as a special correspondent for The Times and there remains little doubt, according to historians, that he was really getting a hands-on look into international espionage. The outbreak of World War II however, would see Fleming’s life take a dramatic turn and make his life a real-life spy thriller.

***

“Fleming shaped Bond as a commando-type to create a symbol of British resourcefulness in a time when the country’s political might was waning.”

Fleming in uniform during World War II (Ian Fleming Estate)

Until September 1939, Fleming had been destined for the life of wine, women, and luxury his family’s large fortune accommodated. But the war would turn the unabashed playboy into an unlikely hero of sorts— all thanks, of course, to the meddling of his mother.

Admiral John Godfrey, Director of Naval Intelligence at Whitehall, had put out the word that he was in need of a personal assistant. Evelyn, desperate to cull her son’s wayward ways, appealed to her late husband’s colleague, Winston Churchill to recommend Fleming for the job. With the backing of his mother and Churchill, Godfrey offered Fleming the job. Now known by his code name, 17F, Fleming found himself in the center of British intelligence and aided in the training of secret agents, tracked U-boats, and provided counter intelligence to the British Navy. He was famous for his irreverent, devil-may-care attitude that stood in stark contrast to Admiral Godfrey’s stern and regimented disposition— mimicking James Bond’s adversarial relationship with the strait-laced Head of MI6, “M.”

Sensing Fleming’s ingenuity, Godfrey tasked Fleming with developing complex espionage plans to confound German forces— several of which would end up being used in the Bond novels. These outlandish missions included forging Reichsmarks to disrupt the German economy and sending a radio ship up to the North Sea to broadcast demoralizing anti-German propaganda to the German navy. When reports that Hitler was on the verge of invading Spain came in, Fleming made another plan. To keep information flowing from the occupied country, he proposed that a group of British agents in Gibraltar report any intelligence back to Britain and carry out missions to sabotage and disrupt German plans. The name of this operation? GoldenEye.

Admiral John Henry Godfrey during World War II (Imperial War Museums)

Fleming’s crowning achievement however, would be a plan known as “Operation Ruthless.” The idea was that British airmen disguised as a Luftwaffe crew were to crash into the north Atlantic using a captured German plane and get the attention of a nearby German ship. Once on board, the British airmen would shoot out the German crew and seize the codebook from a German Naval Enigma Machine. While Godfrey would eventually dismiss this plan, the idea did put Fleming in contact with a man named Charles Fraser-Smith.

Fraser-Smith was an inventor, civil servant, and former missionary who worked for the Ministry of Supply. His work consisted of fabricating equipment, or what we would call “gadgets,” nicknamed “Q-Devices” (as in Bond’s “Q”) for British agents operating in occupied Europe. Some of these gadgets included a shaving brush that could be unscrewed to store important materials such as a map or a compass and a pack of “Garlic chocolates”— pieces of chocolate with bits of garlic so that the British agents would smell like continental cuisine immediately upon arriving in hostile territory. Fraser-Smith and his gadgets would ultimately inspire Fleming when creating characters like Q and villains like From Russia With Love’s Rosa Klebb, the SMERSH agent who infamously concealed a knife in her shoe tip.

One of Charles Fraser-Smith’s designs— a map hidden inside a personal grooming kit (Tangmere Military Aviation Museum)

While Fleming may have got his position with Admiral Godfrey due to the meddling of his mother, his own wit and intellect made him of a favorite of British government officials. Churchill in fact appointed Fleming to answer his urgent intelligence requests and Godfrey later wrote: “I shared all secrets with him, so that if I got knocked out, someone else would be left to pick up the bits.” The British Government was not the only governing body impressed with Fleming’s abilities. In 1941, Fleming liaised with Colonel “Wild Bill” Donovan, Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s special representative on intelligence cooperation between London and Washington. Along with Admiral Godfrey, Fleming lent his hand to writing the blueprint for the Office of the Coordinator of Information— later turned into the Office of Strategic Service and then, the C.I.A.

Another aspect of Fleming’s time in British intelligence that would make its way into the Bond novels is the geopolitics of mid-twentieth century Europe. Nearly all the classic Bond villains, and even some of the Daniel Craig-era Bond films, are of German or Russian decent. According to historian James Taylor of the Imperial War Museum, this is not a coincidence. The iconic Bond villain Blofeld and his mountain hideaway evoke Hitler’s own mountain retreat, Berghof, and are, according to Taylor, Fleming “using shorthand to reawaken reader’s fears.” Furthermore, Fleming’s role in the organization of 30 Assault Unit— a team of comprised of the Marines, the Navy, the Army, and the Air Force— was instrumental in his creation of Bond. The role of this commando unit was to seek and destroy enemy materials, such as weaponry and documents. Like Bond, each man involved had a special skillset, including hand-to-hand combat and expert marksmanship. According to Taylor,

“Fleming always said that Bond was an amalgam of the tough, commando types that he encountered during the second world war and when he was talking about tough commando types, he was talking about 30 Assault Unit. They showed immense pluck, guile, and resourcefulness.”

Considering the industrial might of superpowers like the U.S.S.R. and the United States, Fleming shaped Bond as a commando-type to create a symbol of British resourcefulness in a time when the country’s political might was waning.

After the war ended in 1945, Fleming returned to journalism, becoming the foreign manager in the Kemsley newspaper group, which then owned The Sunday Times. His contract allowed him to take three months’ holiday every winter in Jamaica— where he would ultimately use the events from both his personal and professional life to write “the spy novel to end all spy novels.”

***

“The character and personality traits of the novel’s famous spy were based on several individuals Fleming had met while working in the Naval Intelligence Division.”

L: Ann Fleming (neé Charteris) prior to her marriage to Ian. R: Goldeneye in Jamaica (Ian Fleming Estate)

In 1942, Fleming attended an international intelligence summit in Jamaica and instantly fell under the spell of the island’s natural beauty, despite the heavy downpours that accompanied his visit. He said,

“when we have won this blasted war, I am going to live in Jamaica. Just live in Jamaica and lap it up, and swim in the sea and write books.”

Following through on the promise he made himself, Fleming designed and built a one story bungalow-style house in Saint Mary named Goldeneye. Here, he found himself entertaining a wide variety of guests, including longtime friend and lover, Ann Charteris.

Fleming had begun an affair with Ann Charteris, wife of Shane O’Neill, in 1938. Like Fleming, Charteris came from a long line of British elites and had married O’Neill shortly after her society debut in 1932. In addition to her extramarital affair with Fleming, Charteris also began an affair with Lord Esmond Cecil Harmsworth— the heir to the 1st Viscount Rothermere, who owned The Daily Mail. After her husband was killed in action in 1944, Fleming provided Charteris with a shoulder to cry on, but confirmed to the life of a bachelor however, he refused to marry her. Unwilling to wait for Fleming, Charteris married Lord Rothermere in 1945. Despite her remarrying, Fleming and Charteris continued their affair at Goldeneye with Charteris telling her husband she was visiting her friend, playwright Noël Coward— whose homosexuality was common knowledge among the English elite.

Tragically, in 1948, Charteris gave birth to her and Fleming’s stillborn child, Mary. The loss was a devastating blow to Fleming who, seeing as Charteris carried on as if the baby was her and Lord Rothermere’s, grieved alone. After learning of her affair with Fleming however, Lord Rothermere at last divorced Ann in 1951 and she and Fleming quickly married on March 24, 1952 in Jamaica. In August that year, their son, Caspar, was born.

To distract himself from this sudden loss of his bachelorhood, Fleming sat down to write what would become the first book in the Bond series— his “dreadful oafish opus,” Casino Royale.

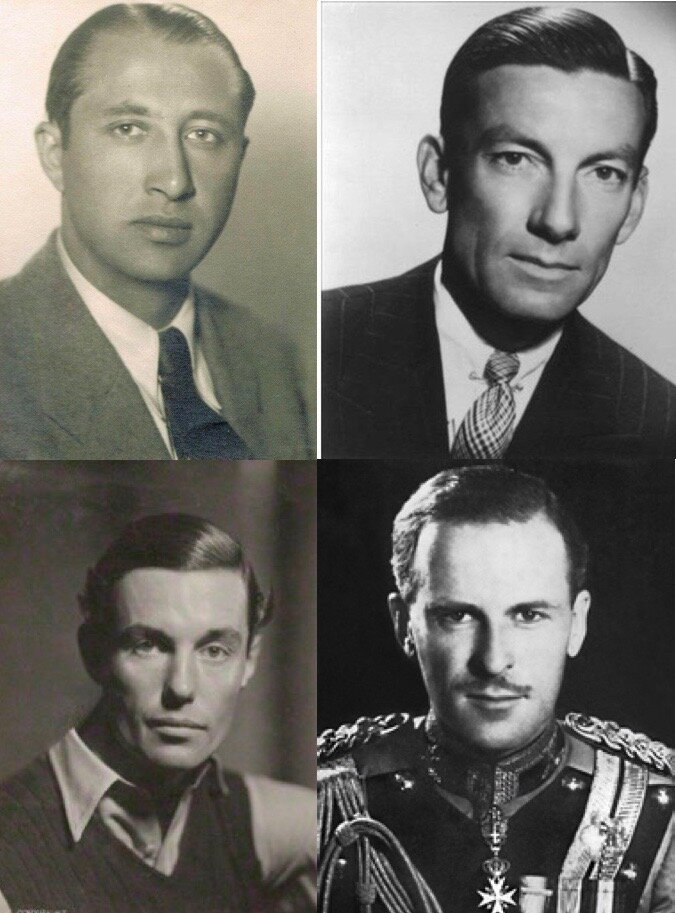

Top Left: Duško Popov in 1940 (National Archives and Record Administration). Top Right: Wilfred “Biffy” Dunderdale (Alchetron). Bottom Right: Formal portrait of Conrad Fulke Thomond O’Brien-ffrench, Marquis de Castelthomond (John Ffrench). Bottom Left: Peter Fleming portrait (Fleming estate)

Drawing on inspiration from his exploits in World War II, Casino Royale tells the story of MI6 Agent Bond attempting to bankrupt Russian secret service member, Le Chiffre, in a game of baccarat. The character and personality traits of the novel’s famous spy were based on several individuals Fleming had met while working in the Naval Intelligence Division.

Among these bold and daring men were Conrad O’Brien-ffrench, 2nd Marquis de Castelthomond. He was a member of the British Secret Service who used a variety of different businesses as cover for his work in espionage. One of these business Tyrolese Tours offered tours from Austria to Southern Germany, where he met Fleming while skiing. Both were gathering information on German troop deployments, but had known one another through various friends and acquaintances for several years. It was O’Brien-ffrench’s intelligence and Clark Gable-like looks that are said to have, in part, inspired 007. Another Bond inspiration was Patrick Dalzel-Job, a British naval intelligence officer and commando who was also a linguist, author, and skiing enthusiast. Despite his reputation as a modest man, Dalzel-Job’s rebellious nature and refusal to obey orders that went against his gut instinct are said to have created Bond’s devil-may-care attitude. For example, while serving with the Anglo/Polish/French Expeditionary Force to Norway, Dalzel-Job disobeyed a direct order to cease civilian evacuations from the town of Narvik, Norway— an action which saved some 5,000 civilians. For this act, Dalziel-Job was awarded the Ridderkors (Knight’s Cross of St. Olav by King Haakon of Norway). When asked about his connection to Bond, Dalziel-Job replied that he had neither seen a Bond movie nor read a Bond book, adding that they were simply “not [his] style.”

Next in Fleming’s long list of muses is Wilfred “Biffy” Dunderdale, station head of MI6 in Paris, whose impeccable style and sartorial flair inspired Bond’s signature style. Dunderdale was almost never seen without a handmade suit on and, while in Paris, saw to it that he was chauffeured around the city in a Rolls-Royce.

In creating the plot of Casino Royale however, Fleming found inspiration in the harrowing stories of colleague Duško Popov. Popov, a Serbian-born triple agent, served as part of Serbia’s VOA (Serbia’s Secret Service Agency), Britain’s MI6, and Abwehr, Germany’s military intelligence service, during World War II. Possessing a strong aversion to Nazism, Popov infiltrated Abwehr, after they allowed him to join based on his business connections in France and the U.K. Under the supervision of France and the U.K., Popov’s job was to pass off false information to Germany. What really inspired Fleming however was Popov’s placing a bet of $40,000 in a game of baccarat at the Estoril Casino in Lisbon, so that a rival agent would withdraw from the game— a move right out of Casino Royale. Additionally, Popov was also something of a womanizer and many believe that Popov’s sexual prowess was a massive inspiration behind Bond’s similar sexual proclivities.

L: Illustration commissioned by Fleming of James Bond. R: Hoagy Carmichael, an American musician whose looks characters in the Bond novels often compare to Bond’s.

While there are several other names historians believed inspired James Bond, Fleming’s true muse was his own brother, Peter. Peter Fleming was an expert on military intelligence and irregular warfare with a never-ending well of thrilling adventure stories for his younger brother to take inspiration from. For example, in April 1932, Peter travelled to Brazil to help in the search for Colonel Percy Fawcett, who’d gone missing in 1925. In a move right out the Bond playbook, Peter and several others created their own search party after a disagreement over the mission’s objectives. In addition to his adventures in South America, Peter also travelled across Asia— going from Moscow to Peking as a special correspondent for The Times.

At the outbreak of World War II, the War Office research section recruited Peter to develop ideas in assisting Chinese guerrillas in the fight against the Japanese army. Adding to his impressive resume, Peter also served behind enemy lines in Norway, initially working with prototype commando units, but eventually becoming a researcher of defense tactics. In the later years of the war, Peter served in Greece before heading to New Delhi to serve as head of D Division, a military deception operation in Southeast Asia. Peter eventually retired in Oxfordshire after the war and became a paternal figure to his nephew, Caspar, following Ian Fleming’s death in 1964.

While there were several other people in Fleming’s life whose likeness he used for other Bond characters (for example, his red-headed secretary, Joan Howe, inspired Moneypenny), it was the talents, feats, and charm he found in himself and those he’d met along the way that helped him to create one of the most iconic characters the world has ever known.

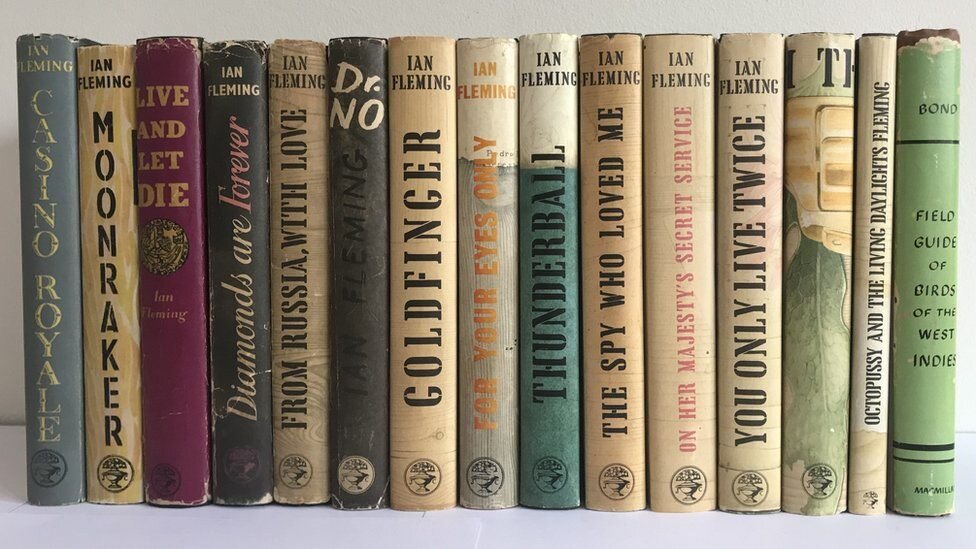

After its publication on April 13, 1953, Casino Royale and the subsequent Bond books flew off the shelves of bookstores all over the world. Though film offers came pouring in, it would not be until almost a decade later in 1962, when the Sean Connery-led Dr. No hit theaters, that Bond would make his big-screen debut and become nothing short of a pop-culture icon.

Set of first edition James Bond novels (BBC)

“Watching Bond constantly disobey the orders of M and his corporate bosses as well as his refusal to adhere to anyone’s strict codes other than his own empowered western audiences of the early 1960’s.”

Though Fleming died of a heart attack in the early morning hours of August 12, 1964 (incidentally, his son Caspar’s birthday), his published work— which includes the children’s classic Chitty Chitty Bang Bang— continues to enrapture audiences all over the world. For years, critics and audiences alike have postulated several reasons for Bond’s longevity. Some argue its success can be linked to quelling modern-day fears about the rise of the machine. For others however, like sociologist Thomas Andre, the Bond films provide audiences, particularly male audiences, a means through which to assert their autonomy from the soul-crushing landscape created by modern corporations. Andre argues that 1962, the year of Dr. No’s release, presented a “crisis of masculinity” and that the men who had once been so young and idealistic in the post-war years now found themselves selling out their autonomy for a monotonous corporate life. Unlike Bond, they had become a simple cog in a vast machine and for them, spy-thrillers became the perfect means for escape. Watching Bond constantly disobey the orders of M and his corporate bosses as well as his refusal to adhere to anyone’s strict codes other than his own empowered western audiences of the early 1960’s.

For some critics however, Bond — both on film and in print— is outdated and regressive. Paul Greengrass, director of two of the Jason Bourne spy films, accused Bond of being “a misogynist, [and] an old-fashioned imperialist.” Meanwhile, novelist Louise Welsh in her introduction of Live and Let Die has claimed that the novel and films “tap into the paranoia that some sectors of white society were feeling” as the civil rights movement in both the U.S. and in the U.K. challenged prejudice and inequality.

Criticisms such as these are far from the most scathing critiques of the Bond franchise, particularly of the earlier books and films. In fact, even in 1995’s Goldeneye, the first film to star Pierce Brosnan as 007, M (now played by actress, Judi Dench) calls Bond a “sexist, misogynist dinosaur [and] a relic of the Cold War.” The Daniel Craig-led films have in earnest tried softening Bond’s more problematic elements from earlier iterations. For example, female characters like Casino Royale’s Vesper Lynd (played by Eva Green) and Dr. Madeleine Swann (played by Léa Seydoux) are given significantly more agency and the upcoming No Time To Die boasts comedy superstar, Phoebe Waller-Bridge as one of its writers. Moreover, the newer Bond films go out of their way to assert the franchise’s relevance. 2012’s Skyfall offers a scene in which Dench’s M defends MI6 at a Parliament inquiry. Right before a group of terrorists attack the British Parliament, she remarks the lack of safety within the intelligence world. Several scenes later, after fleeing this scene in his iconic Aston Martin DB5, Bond muses that “sometimes the old ways are best”— reaffirming to the audience its need for Bond.

L-R: Sean Connery, George Lazenby, Roger Moore, Timothy Dalton, Pierce Brosnan, Daniel Craig (Getty Images)

With these valid criticisms in mind, the question becomes: why does James Bond continue to resonate with audiences long after his initial heyday and after substantial criticism? Why does each new Bond film continue to generate billions of dollars in revenue? The answers all comes back to Ian Fleming. Thomas Andre was correct in saying that the Bond films are indeed the perfect tonic for the humdrum of daily life. Not all of us can live the dramatic lifestyles Ian Fleming and the men he based his famous spy on lived. If we can’t live lives full of intrigue, passion, danger, and style, we can at least live through them vicariously through Fleming’s avatar of his own self. In using the experiences of those he admired in addition to his own, Fleming gave us the ultimate aspirational character. We all wish we were a little bit more like James Bond. We wish we could be as cool and collected as he is when he’s facing an enemy like S.M.E.R.S.H. We long to have his quick wit, his effortless charm, and understated, but nonetheless irresistible sensuality. Ultimately Bond gives us the instructions on how to, and (especially in earlier films) how not to, be cool, classy, tough, and manly in a world that consistently tries to wear us down.

Portrait of Fleming (Getty)

So, as long as the Bond franchise continues to evolve for the better and allows us to imagine a better, more fashionable, version of ourselves, then Bond (like diamonds) is certainly forever.

Consider this my audition reel for the next Bond franchise…

Sources and References:

Chancellor, Henry. James Bond: The Man and His World. John Murray, 2005.

“First Trip to Jamaica.” Ian Fleming, https://www.ianfleming.com/ian-fleming/.

Fleming, Ian. Casino Royale. Ian Fleming Ltd, 1953.

Fleming, Ian. Live and Let Dine. Ian Fleming Ltd, 1954.

Fleming, Ian. On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. Ian Fleming Ltd., 1963.

“Ian Fleming.” Biography, written by Cindy Robinson and Addey Mitchell, A&E, 2006. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wtAyviHxzLE&t=1750s

“Ian Fleming: Where Bond Began.” BBC One, 2008. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r1u5sFBfBKc&t=1481s

Lycett, Andrew. Ian Fleming. St. Martin’s Press, 1995.

Macintyre, Ben. For Your Eyes Only. Bloomsbury, 2008.

Macintyre, Ben. “The Real 007’s Cover Has Been Blown.” The Times, September 25, 2020, https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/the-real-007s-cover-has-been-blown-zjp0vkxsb. Accessed September 2021.

Pearson, John. The Life of Ian Fleming. Bloomsbury, 2011.

Scherker, Amanda. “The Philosophy of Archer.” YouTube, uploads by Wisecrack, 16 December 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mvm8RTdJgq0&t=110s.

Skyfall. Directed by Sam Mendes, performances by Daniel Craig and Judi Dench, Eon Productions, 2012.

Travis, Ben. “Paul Greengrass Says James Bond Films ‘Responded Well’ To Jason Bourne.” Empire, September 6, 2020. https://www.empireonline.com/movies/news/paul-greengrass-says-james-bond-films-responded-well-to-jason-bourne/