THE OG BETH HARMON

Unlike the rags-to-riches narrative of Beth Harmon in "The Queen’s Gambit," Paul Morphy’s story was anything but a Cinderella story.The eyes of the spectators that crisp autumn night in 1858 were supposed to be on the opera— Bellini’s Norma or Rossini’s The Barber of Seville depending on the source. Instead, all eyes at the opera, Salle Le Peletier, were fixed on a twenty-year old chess prodigy from Louisiana who was bringing a German Duke and a French Count to their knees in a chess match. Though Charles II, Duke of Brunswick, and Count Isouard de Vauvenargues were master chess players in their own right, they were no match for intrepid prodigy, Paul Morphy. After a solid effort, the two found their king overpowered by Morphy’s rook after Morphy sacrificed his queen to provide his rook a clear path to checkmate. Though the match then was seen as just a chess match between an exciting foreign prodigy and two noble amateurs, it would come to be known as one of the most famous matches in the nearly fifteen-hundred year history of chess.

Commonly referred to as “The Opera Game,” this particular match is a staple for chess instructors, teaching the importance of rapid development of a players pieces and the value of sacrifices in mating combinations. Indeed, Paul Morphy’s performance in this match also illustrates the most important concepts of modern chess such as development (moving your pieces out from their starting positions), mobility (the number of choices a player has at a given position), initiative (being on the offense), and the founded attack (or, direct attack). In the twenty-first century, the famous Opera Game has another claim to fame— being among the many inspirations for the smash hit miniseries, The Queen’s Gambit. Since premiering on Netflix in late October of last year, The Queen’s Gambit has become nothing short of an international phenomenon— streaming to over 62 million viewers in its first month of release, and garnering a series of accolades including two Golden Globes, two Critic’s Choice Awards, and a Screen Actors Guild award. While a vast portion of the reviews have lauded Anya Taylor Joy’s magnetic performance, the sharp writing, and exquisite production values, the series also attracted praise from the chess community for its accuracy in depicting the game. In an interview with Vanity Fair, FIDE (International Chess Federation) Women’s Grandmaster Jennifer Shalade stated that the series “completely nailed the chess accuracy,” while in an article for The Times, British chess champion David Howell described the chess scenes as “well choreographed and realistic.” Even a more critical voice like Grandmaster Nona Gaprindashvili (who the series falsely claims to have never faced a male component) praised the show for accurately portraying the pressures of professional chess. Part of the reasoning for the series’ undeniable accuracy is the fact that several of its most important games were lifted move-for-move from real chess matches— including the famous “Opera Game” depicted above, which Beth Harmon and Benny Watts’ chess game in the series’ sixth episode mimics.

Two other notable games which The Queen’s Gambit borrows its moves and results from are a 1955 match between Rashid Nezhmetdinov and Genrikh Kasparian in Riga, Latvia and another played in Biel, Switzerland by Vasiliy Ivanchek and Patrick Wolff. While the former game inspired the early scene in the series in which protagonist Beth Harmon beats Henry Beltik in the state championship, the latter match inspired the series’ epic climax in which Beth beats Russian champion Vasily Borgov. Each of these players are success stories in their own right, but none are as influential, or as enigmatic, as Paul Morphy— the original Beth Harmon.

Unlike the rags-to-riches narrative of Beth Harmon in The Queen’s Gambit, Paul Morphy’s story was anything but a Cinderella story. Morphy was born in New Orleans, Louisiana on June 22, 1837 to Alonzo Michael Morphy and Louise Thérèse Félicité Le Carpentier, or “Telcide” for short. His father was a lawyer who served as a Louisiana state legislator, then as Attorney General, and ultimately as a Louisiana State Supreme Court Justice. Paul’s mother, Telcide, was born to a socially prominent French Creole family. Their home at 1113 Chartes Street was a stately property that later became home to Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard, a Confederate General, and was then bought by author Francis Parkinson Keyes. When Morphy was four, his parents moved the family into a mansion at 89 Royal Street — now the site of the celebrated New Orleans restaurant, Brennan’s. It was here in this stately southern manor, that Morphy’s knack for chess took shape. According to legend, Morphy never took a formal chess lesson. Instead, on Sunday evenings, Telcide gathered the family together for an evening of music, reading, and games— including chess. Ernest Morphy, Paul’s uncle, claimed that his nephew absorbed the rules and nuances of the game simply by observing others play. By Ernest’s account, the child’s skill came to light one evening as Ernest and Alonzo abandoned a chess game— calling it a draw. As the two stood up to tend to other tasks, young Paul surprised the two of them by stating that Ernest should have won. In disbelief that a young child could know such a thing, they asked him to prove it. Paul subsequently reset the pieces the way they were and demonstrated the win his uncle had missed. Astounded, Paul’s uncle encouraged him to continue playing at family gatherings and local chess matches— ensuring his nephew’s position as one of New Orleans’ top players by the time he was nine.

Paul Morphy (left) and a friend playing chess (Smithsonian, 2011)

That year, Paul Morphy defeated Commanding General of the United States Army, Winfield Scott at the Royal Street Chess Club, where the General had come to “be put to [his] mettle” in a game of chess. When asked to meet his chosen competitor, General Scott thought that the child in front of him a joke. But when Morphy beat the General not once, but twice, the General realized he was anything but. Four years, at age twelve, later Morphy would go on to defeat Hungarian chess master, Johann Löwenthal, who was visiting New Orleans and looking for a child to play. Morphy ended Löwenthal in just twelve moves.

After these early victories, Morphy’s chess career lay dormant for many years as he received a degree in math and philosophy from Spring Hill College in Mobile, Alabama. In May 1855, he was awarded high honors from the college and went on to receive a law degree from the University of Louisiana (now known as Tulane University). While in school, his intelligence mystified his professors and classmates and it was even rumored that he memorized the entire Louisiana Civil Code while at law school.

Just as Beth Harmon’s adoptive mother, Alma, encouraged her daughter’s chess career in early episodes of The Queen’s Gambit, Morphy’s Uncle Ernest remained instrumental in encouraging his nephew to pursue a career as a professional chess player. At his uncle’s insistence, Morphy entered the First American Chess Congress in the late fall of 1857— where Morphy went on to defeat both domestic and international masters of the game in the final rounds of the tournament. In an instant, Morphy became the greatest chess player in the United States. With what the December 1857 issue of Chess Monthly called a “genial disposition… unaffected modesty and gentlemanly courtesy,” Morphy won not just his matches, but the respect of his opponents as well.

While the toast of the American chess world, the true test of Morphy’s mettle would be how well he’d fare in Europe— where nearly all of the world’s most formidable chess competitors lived. Too young to legally practice law in the United States, Morphy travelled to England after a period of intense negotiation between Europe and the American Chess Association. Unlike the 1960s setting of The Queen’s Gambit where European players flocked to American tournaments, European competitors in the 1850’s were far less eager to travel to the United States— where chess was considered much more of a niche pastime. In order to convince their European cohorts, the American Chess Association announced a challenge to any European player, offering a $2,000 to $5,000 prize to anyone who would travel to New York City and beat the prodigy Paul Morphy. When interest remained stagnant, The New Orleans Chess Club offered a challenge to European champion Howard Staunton. Staunton was then regarded as the world’s strongest chess player after defeating French chess master Pierre Charles Fournier de Saint-Amant and had been the principal organizer of the first international chess tournament in 1851. Staunton, via The Illustrated London News, stated that it was impossible for him to travel to the United States and if Morphy wanted to play, Morphy must travel to Europe.

“If Mr. Morphy— for whose skill we entertain the liveliest admiration— be desirous to win his spurs among the chess chivalry of Europe, he must take advantage of his purposed visit next year; he will then meet in this country, in France, in Germany, and in Russia, many champions whose names must be as household words to him, ready to rest and do honor to his prowess.” — Staunton, The Illustrated London News, 3 April, 1858

Hellbent on winning, Morphy ventured across the Atlantic to England and made several attempts to liaise with Staunton— who seemed equally as hellbent on avoiding Morphy at all costs. Staunton received a fair amount of criticism for avoiding Morphy, including reports that Staunton was afraid of being past his prime. Staunton retaliated by stating Morphy didn’t have the money for the proposed financial stakes of the match. Given Morphy’s emerging celebrity, as well as his family background, everyone knew this was far from the case. While Staunton remained unmoved, the European chess masters were clamoring for a spot to compete against this rising American prodigy. Traveling to France, Morphy defeated chess professional, Daniel Harrwitz at the famed Café de la Régence. He then defeated German master Adolf Anderssen, over a period of eight days in December 1858, even after suffering severe blood loss from being treated with leeches after a nasty bout of stomach flu. It is during this tour that Moprhy competed in the famed “Opera Game” against the Duke of Brunswick and Count Isouard. With the success of this European tour under his belt, Paul Morphy was now a bonafide celebrity and a world renowned prodigy. He had beaten the world’s greatest chess players, been extended an invitation to play at the Imperial Palace in Saint Petersburg, and was granted an audience with Her Majesty Queen Victoria herself.

Upon returning to the United States, Morphy’s victory tour included a stop in New York, a banquet attended by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and the first family proclaiming him “Paul Morphy: Chess Champion of the World.” He drew the attention of popular brands who asked for product endorsements and newspapers solicited him for chess columns. Indeed, at just twenty one years of age, Morphy— like his fictional counterpart, Beth Harmon— had taken over the world. However, like Beth in The Queen’s Gambit, Morphy would eventually succumb to the demands of fame and learn that the only place to go when you’re at the top is down.

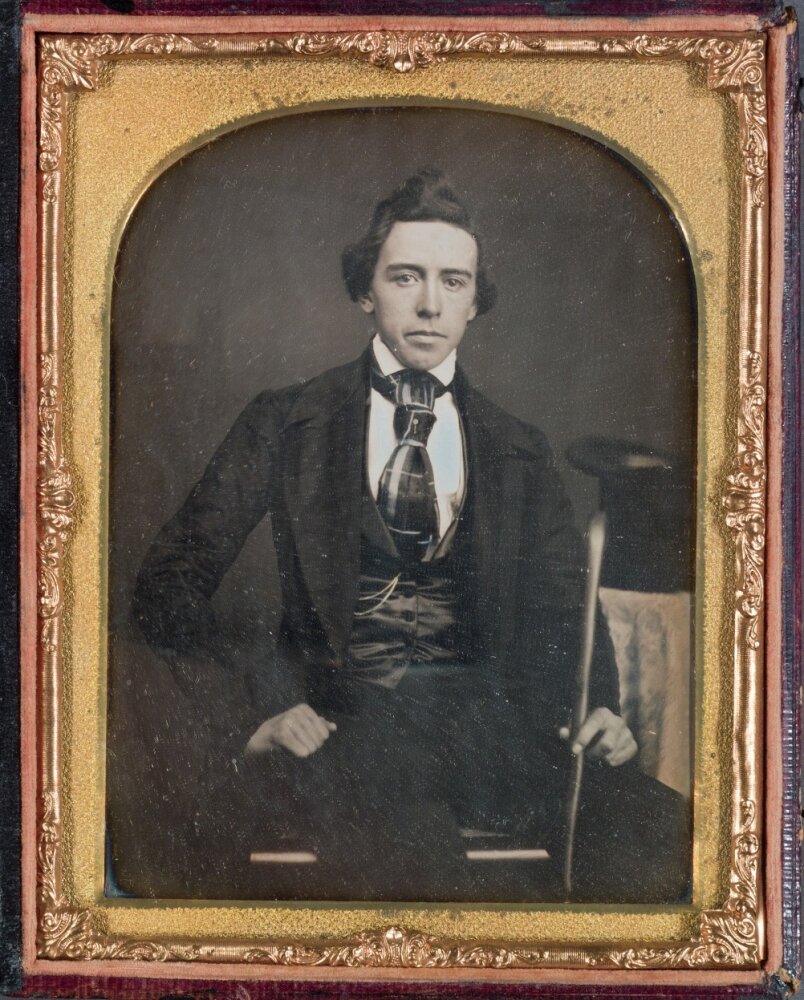

Daguerrotype of Paul Morphy,

1857-1859. The Historic New Orleans

Collection. Tobacco advertising endorsement by Paul Morphy, source unknown.

With the advent of the Civil War, much of the Morphy family, including Paul, fled the now Confederate States of America. The law career he had been slowly developing was set aside and his mother and sisters fled to Paris. Historians have argued as to whether or not Morphy was involved in the Confederate army. In his book Paul Morphy: The Pride and Sorrow of Chess, David Lawson argues that he may have been on P.G.T. Beauregard’s staff for a brief period of time. This story, according to Lawson, was corroborated by a resident of Richmond, Virginia describing the famous Morphy as a member of Beauregard’s staff in 1861. Other reports claim that Morphy was under-qualified for military service under Beauregard and other sources claim he had fled to Havana from 1862-1864 and joined his mother and sisters for a brief while in Paris. When the war at last ended on April 9, 1865— Morphy’s chess career was long dead. Opting for job security as the nation reeled from the cultural and economic impact of the war, Morphy founded his own law firm. After many clients wished to only discuss, or even play, chess with the great champion himself, the practice failed. Nobody could take the man seriously as a lawyer. Even his personal life could not escape the shadow of his storied reputation: a wealthy society girl of New Orleans refused to marry him for being a mere chess player. As the years passed, Morphy grew more and more detached from the game that had made him a celebrity. To him, chess was akin to a shady activity such as gambling, and was “not a real profession.”

While his father and mother’s fortunes afforded him the luxury of not having to work, offers to play chess were many. Sadly, by this time, Morphy’s mental state had began to rapidly deteriorate and he fell into a period of delusion and paranoia. He wandered the streets of New Orleans, loudly talking to himself and going off on some long-winded tirade. His colleague, Charles Maurian noted in many letters that Morphy was “deranged” and “not in the right mentality.” He refused to be admitted to any retreat or sanitarium— in fact, so coherent and persuasive was his speech that many professionals at these various institutions sent him away. His delusions came to a tragic conclusion one afternoon in late summer. On July 10, 1884, Paul Morphy was found dead in his bath tub, having suffered a stroke in the ice cold water according to autopsy reports. The greatest chess player in the United States, a child prodigy who had played for King and Queens, was dead at just 47.

In The Queen’s Gambit, Beth Harmon muses that “chess isn’t always competitive,” adding that “chess can be beautiful.” There are many ways in which this quote applies to the narrative of both Beth Harmon and Paul Morphy. While their stories both involve becoming international chess stars at a very young age, they also provide a window into the beautiful, chaotic, high-stress, and very high-stakes world of competitive chess. While Morphy viewed chess as just a pastime, the game would eventually evolve into one of the most lucrative, yet infrequently discussed competitive games in the world. In 1924, a campaign was started to have chess become an official olympic sport. When this campaign failed however, the chess world convened in Paris and played the first ever Chess Olympiad at the Hotel Majestic from the 12-20 of July. At the end of this first tournament, the Fédération Internationale des Échecs (known as FIDE) formed on the event’s closing day. In 1927, the next Chess Olympiad, there were sixteen participating countries, by 1990 there were 127. At the most recent Olympiad in 2018, there were 185. Meanwhile prize earnings now reach over $1 million. With The Queen’s Gambit becoming the surprise hit of the year, it seems only natural that the popularity of the game will continue to grow around the world and more Beth Harmon and Paul Morphy’s await to take the game of chess, and the world, by storm.

Sources and References:

Edge, Frederick Milnes. “The Exploits and Triumphs, in Europe, of Paul Morphy, the Chess Champion.” D. Appleton & Company, 1859.

Franklin, Gustavo Leite, Brunna N.G.V. Pereira, Nayra S.C. Lima, Francisco Manoel Branco Germiniani, Carlos Henrique Ferreira Camargo, Paulo Caramelli, Hélio Afonso Ghizoni Teive. “Neurology, psychiatry and the chess game: a narrative review.” Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria, vol. 78, no. 3, 2020, https://www.scielo.br/j/anp/a/CWFYKTTWwVJHN7kbCyrWy7q/?lang=en#. Accessed May 2021.

Gobet, Fernand. The Psychology of Chess. Routeledge, 2018.

Kurtz, Michael L., “Paul Morphy: Louisiana’s Chess Champion.” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association, vol. 34, no. 2, 1993, pp. 175-199, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4233011. Accessed June 2021.

Rotov, Dimitri. “Winfield Scott loses a match.” Civil War Bookshelf, http://cwbn.blogspot.com/2007/03/winfield-scott-loses-match.html.

Winter, Edward. “Memory Feats of Chess Masters.” Chess History, https://www.chesshistory.com/winter/extra/memory.html.

Winter, Edward. “Morphy v the Duke and Count.” Chess History, https://www.chesshistory.com/winter/extra/morphy.html.